Access Pathway for Innovative Medicines in China: Basic Social Medical Insurance

To understand the access pathways for innovative medicines in China, we have to follow the money.

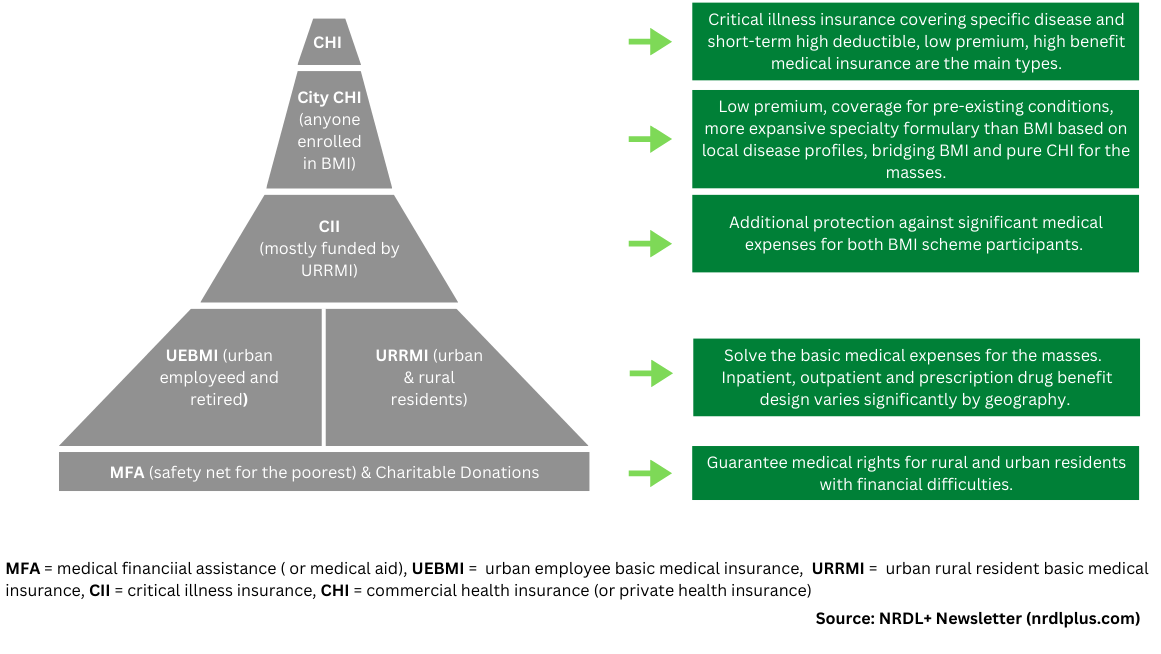

Three layers in China’s medical security system play a crucial role in funding innovative medicines, each with its own target positioning.

• Basic Social Medical Insurance (BMI) Schemes. BMI provides inpatient, outpatient, and prescription drug benefits to address the basic medical needs of the masses.

• City Commercial Health Insurance (City CHI). Operated through a public-private partnership, positioned between BMI and pure commercial health insurance, City CHI aims to further alleviate out-of-pocket (OOP) expenses associated with inpatient services and specialty drugs for BMI participants.

• Commercial Health Insurance (CHI). CHI is designed to satisfy the diversified healthcare needs of Chinese consumers, especially the middle class. The main types are personal critical illness insurance for specific diseases and short-term, low premiums, high-deductible, and high-benefit medical insurance.

We will start with the BMI route in this three-part series of access pathways for innovative medicines in China.

Figure 1: China’s Multi-Layered Health Financing Ecosystem

Basic Social Medical Insurance Schemes

This layer comprises urban and rural resident-based and urban employment-based basic medical insurance schemes designed to solve the basic medical expenses for the masses, including inpatient, outpatient, and prescription drug benefits.

Government subsidies primarily fund the urban and rural resident-based scheme (70%), and employer and employee contributions fund the urban employment-based scheme. Innovative medicines included in China’s National Reimbursement Drug List (NRDL) are covered and reimbursed by BMI. This, however, excludes innovative vaccines. Vaccines are financed from a separate public health service package.

BMI covers more than 95% of China’s 1.4 billion population. According to IQVIA data, the average reimbursement ratio for NRDL-negotiated drugs (i.e., innovative medicines) was 68.7% as of 2021. However, BMI benefits are administered locally; as such, actual coverage and reimbursement can vary widely across insurance schemes and regions in China.

For instance, a recent survey conducted by China Development Research Foundation, a State Council-affiliated economic think tank, revealed significant regional differences in out-of-pocket (OOP) expenses for NRDL-covered cancer therapies, ranging from 1.75 to 2.7 times a household's average annual disposable income.

In the past, aside from the NRDL, some provinces (Qingdao, Jiangsu, Jiangxi, Zhejiang, etc.) also negotiated their own drug list (PRDL). PRDL was allowed a 15% variation from the NRDL Class-B scope (i.e., innovative drugs). Local-level negotiations often preceded the national negotiation, which offered referential experience and lessons for the national negotiation.

However, in July 2019, the National Healthcare Security Administration (NHSA), which is responsible for administering all social insurance schemes, issued a policy memo that discussed the need for a unified national formulation of the drug reimbursement list, thus, removing the authority of provincial governments to adjust the NRDL Class B listing.

At the end of 2022, all provinces must strictly follow the NRDL, which has effectively closed provincial access routes for innovative medicines with BMI funding.

Provincial Critical Illness Insurance

The urban and rural resident-based scheme funds provincial Critical Illness Insurance (also called catastrophic medical insurance), compensating BMI participants whose OOP expenses have exceeded the reimbursement ceiling under the BMI schemes due to critical illness.

The definition, coverage scope, and reimbursement ratios for critical illness vary across regions.

Some provinces (e.g., Zhejiang, Jiangsu) have supplemented Critical Illness Insurance with non-BMI funds to provide coverage for rare disease therapies not listed in the NRDL.

Medical Aid

The medical aid programs, funded by central and local governments and charitable donations, provide a further safety net for the poorest in China by paying their medical insurance premiums and reducing OOP expenses after receiving reimbursement from basic social health insurance schemes and critical illness insurance.

NRDL Negotiation: Price and Volume Trade-Off

Since 2017, the National Reimbursement Drug List has been updated annually, adding 394 innovative drugs to the BMI catalog in six years, including 67% of orphan drugs targeting disease conditions listed in China’s first National Rare Disease List.

The NRDL remains the most impactful access route for manufacturers who want to access China’s 1.4 billion consumer market.

And NHSA knows it. It also shows in the data.

According to IQVIA data, the average price discount for NRDL-negotiated drugs (i.e., innovative therapies) was 44%, 56.7%, 60.7%, 54.3%, 61.7%, and 60.1% from 2017 to 2022, respectively. And the corresponding average sales growth for NRDL-negotiated western drugs was 170%, 720%, 530%, and 390% from 2017 to 2020, respectively.

However, the price-volume trade-off strategy has its challenges.

For multi-source products facing severe competition, further price erosion under NRDL can be too much for manufacturers to bear. For instance, China’s NRDL route seems to be a dead end for foreign, even some local PD-1/L1 inhibitors.

For single-source products with superior clinical value truly addressing critical unmet needs, some have successfully launched in China without an NRDL listing.

The same is true for products targeting small patient populations. The price-volume trade-off can prove challenging for both NHSA and manufacturers.

Emerging commercial pathways hold great promises for these products, as discussed later in this access pathway series.

It has been reported that 20 innovative products from domestic and international manufacturers have decided to forgo the opportunity to participate in the 2022 NRDL negotiation because of pricing and hospital access issues discussed below, at least for now.

The “Last Kilometer” Problem

Inclusion in NRDL is merely the beginning of the access journey in China for manufacturers.

For example, one of the most significant advantages of an NRDL listing is quicker product uptake at China’s public hospitals, which account for about half of China’s Total Health Expenditure (THE).

However, it is easier said than done. It has become common that certain NRDL products have difficulty accessing hospital formularies, hence the ‘last kilometer’ problem.

The China Pharmaceutical Association surveyed 1,420 hospitals in 2021, showing that only 25% of the innovative cancer drugs listed in the NRDL between 2018 and 2019 were used in hospitals.

The reasons why the “last kilometer” problem exists are complex. Yet at the core, it is about $ or ¥ in this case. Drugs are no longer a profit center for public hospitals in China since the removal of medicine markup at public hospitals nationwide in 2017. Yet many NRDL-negotiated drugs are associated with special handling and storage requirements, which can add to a hospital’s administrative costs with no off-setting revenue. This profit squeeze will likely intensify with the sweeping hospital payment reform.

As a result, even when NRDL-negotiated medicines are excluded from a hospital’s budget control metrics, there is still not enough incentive for hospitals to add them to their formulary except to meet patients’ demands.

The Dual-Channel policy issued by NHSA in May 2021 has expanded reimbursement coverage for selected NRDL-negotiated drugs from inpatient reimbursement only to including reimbursement at designated outpatient retail pharmacies. The policy aims to facilitate prescription outflow from public hospitals to retail channels and accelerate patient access to NRDL-negotiated drugs.

Implications for Manufacturers

So, what does this all mean for innovative medicine makers?

• Adjust expectations for NRDL negotiation. In pharmaceutical pricing, value-based pricing tends to set the upper limit on a viable price range for a product, and the cost-plus (or ROI) approach tends to fix the lower limit.

NRDL negotiation follows a cost-plus pricing approach for good reasons.

First, China’s basic medical insurance schemes are positioned to solve basic medical expenses for the masses.

Second, as a developing nation, China’s healthcare infrastructure is still maturing, which dictates different policy priorities compared to developed markets.

For instance, the top of the list on China’s healthcare reform agenda is establishing a primary care-based gate-keeping system to improve health system efficiency. In comparison, healthcare infrastructure in the developed markets is relatively mature; thus, value-based pharmaceutical pricing is more common.

As such, it should not surprise global drug makers that NHSA will continue prioritizing budget impact (i.e., affordability) over cost-effectiveness (i.e., value) in the foreseeable future.

• Develop a broader view of affordability. To improve commercial return and sustain innovation for the long term, drug makers need to tap into a multi-layered financing ecosystem emerging in China.

Thanks to a supportive policy environment, commercial health insurance has become a viable pathway for manufacturers to reach hundreds of millions of Chinese consumers at product launches.

As such, commercial health insurance is no longer just a pre-NRDL consideration for innovative drug makers. Instead, it needs to be an integral component of any well-thought-out access strategy throughout the product life cycle in China.

We will devote the rest of this three-part China access pathway series to commercial health insurance.

• Assess implementation capabilities. China is large and diverse. It is not just one country. As a result, policy implementation will inevitably take on regional flavors.

Manufacturers should accurately and objectively assess their implementation capabilities at the local level, whether it's about addressing the "last kilometer" problem with NRDL-covered medications or collaborating with commercial insurers.

References:

- Health insurance systems in China: A briefing note (WHO, 2010)

- China's Health System Reforms: Review of 10 Years of Progress (BMJ article collection, 2019)

- Guidance about the implementation of urban and rural residents’ critical illness insurance system, National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), Ministry of Health (MOH), August 30th, 2012

- White Paper on China Commercial Health Insurance, E & Y, 2018

- City Supplementary Commercial Health Insurance, the Prospering Inclusive Solution for All, https://fintechforhealth.sg/city-supplementary-commercial-health-insurance-the-prospering-inclusive-solution-for-all/, Access Health International, September 8th, 2021

- Key success factors navigating the Asia Pacific market landscape for successful launch and commercialization (Web conference), IQVIA, 11/30/22

- Medicines in China’s National Health Insurance System, China Development Research Foundation, 1/22/2022

- Zhang et al. The Basic vs. Ability-to-Pay Approach: Evidence From China's Critical Illness Insurance on Whether Different Measurements of Catastrophic Health Expenditure Matter, Frontiers in Public Health, March 18, 2021

- Tao et al. (陶立波 et al.) An Analysis and Discussion of Multi-level Medical Security System for Rare Diseases in China (中国罕见病多元保障体系建设的分析与探讨). Journal of Rare Diseases (罕见病研究), January 2023

- European Business In China Position Paper 2020/2021, Pharmaceutical Working Group

- 医保谈判高成功率背后 (Behind the High Success Rate of NRDL Negotiation), https://www.cn-healthcare.com/articlewm/20230121/content-1501289.html, 1/21/2023

- 弥漫在“国谈药“身上的进院焦虑 (The Hospital Admission Anxiety Prevalent among National Negotiated Drugs) https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/QDkt67Tbpm1ZGSIcAc15Kg, China Pharmaceutical Innovation and Research Development Association, 2/15/2023